Reinventing the Kitchen

Since its inception, St. Charles has been a leader in both form and function.

St. Charles New York Creative Director Karen Williams (right) designed the company’s first kitchen collection with a vision for luxury that is simple yet extraordinary. Shown here is STC No. 3.

In the 1930s, kitchens everywhere were draped in natural-hued wood cabinets that had been standard for generations, but a new company based in St. Charles, Illinois, would awaken homeowners to the dual ideas of sleek new materials and color in the kitchen.

“People always referred to ‘a St. Charles kitchen,’” says Karen Williams, creative director of St. Charles. “Everything else was cabinets but you would say, ‘I have a St. Charles kitchen,’ meaning it’s all- inclusive, it’s well-designed, it’s well-engineered. It was the first to be referred to in that way.”

Falling Water: St. Charles is selected for the kitchen at Fallingwater, the iconic cascading waterfall house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in Mill Run, Pennsylvania. PhotograPh courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania conservancy

From the outset, the new design approach and materials found in the St. Charles line struck a chord with notable and modern-leaning designers and architects. The clean lines, color options, and efficiency afforded by the cabinetry’s enameled-steel construction worked with the sensibility of modernism and of contemporary design in general. It’s no surprise then that the company’s line found its way into distinctive homes that immediately secured their places in architectural and design history. In fact, Frank Lloyd Wright’s cascading Fallingwater, Mies van der Rohe’s glass masterpiece the Edith Farnsworth House, and Richard Meier’s geometric Smith House all feature St. Charles kitchens. In the case of Fallingwater, St. Charles was only in its second year of business when it was selected for the kitchen of the soon-to-be iconic home.

1949 Farnsworth: St. Charles is specified for the Edith Farnsworth House (center image), Mies van der Rohe’s iconic glass creation in Fox River Valley, Illinois.

“When you come to the prestigious designers and architects,” Williams says of the bold-faced design names, “I think what St. Charles offered them was an architectural status symbol—a symbol of quality and good design. It’s really the cornerstone of creativity and innovation.”

Williams notes the historic architects were also attracted to the materials the company employed for its cabinetry. “No one was doing steel at that time,” she says. “But offering a baked enamel steel with either a smooth or textured finish went with the crisp clean lines of the architecture that they were looking for. That was really important. It didn’t fight with but rather complemented everything they were putting in the house. I think it was very important to the architects to have something that enhanced what they were doing.”

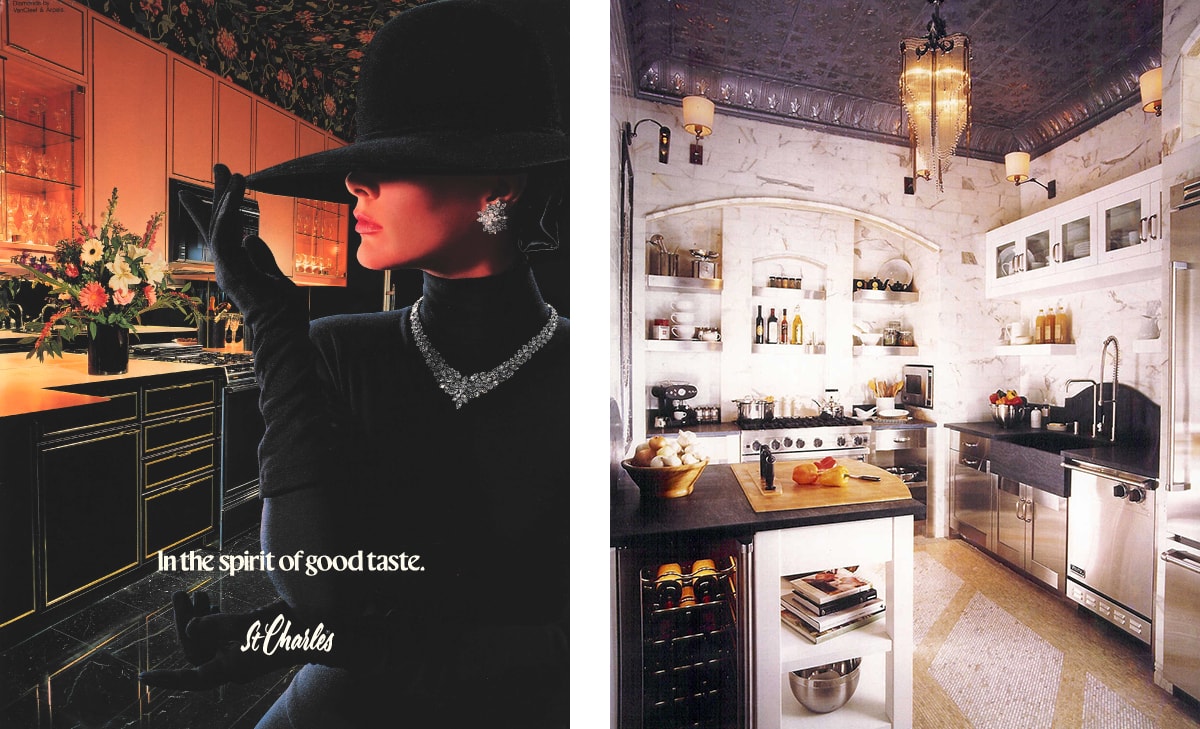

Left – 1988: In good company: Advertising from the 1980s featured a sophisticated woman draped in Van Cleef & Arpels jewelry enjoying her St. Charles kitchen. Right – 2003 Kips Bay: For this tiny bistro-style kitchen in the annual Kips Bay Show House, the space was paved with floor-to-ceiling marble tile. The stainless steel and white cabinetry is accented by charcoal Italian limestone.

That same creative sentiment rings true today for the designers and architects who turn to St. Charles to be a true partner in their projects and for the discerning consumers who continue to value the St. Charles kitchen as a symbol of status and luxury.

Left – 2019: With a new status as inventor, Karen Williams, on behalf of St. Charles New York, is awarded a U.S. patent for the cabinet design of STC No. 1 from the St. Charles Collection. Right – 2020: Continuing to innovate, St. Charles New York launches a new website, new brand identity, and its first kitchen collection: the St. Charles Collection (STC).

“I think the luxury of it is the fact that it was classic, it was iconic, it was definitely very durable—it lasted for 20, 30, 40 years—and it complemented all the different architectures,” Williams says, noting the variety of locations and design styles—from Fallingwater to The Palace Hotel and countless private residences—where the St. Charles kitchen has found an ideal home. “We have been able to maintain that by not compromising. We just consistently offered good design, creativity, and innovation—that’s what comes to mind when I think of quality and luxury. We have never wanted to be everything to everyone. We wanted to be the best at what we were.”